Posted July 27, 2018

For returning audiences, seeing Mark Bedard – a celebrated clown and HVSF fan favorite – in the role of the “bullet-headed” Henry Bolingbroke (Wall Street Journal) in this season’s RICHARD II may come as a bit of a shock. The cut-throat, self-determined Bolingbroke is everything Hortensio (Mark’s parallel role in this season’s THE TAMING OF THE SHREW) , Touchstone (2016’s AS YOU LIKE IT), and Mr. Collins (2017’s PRIDE AND PREJUDICE) aren’t. Mark shares his thoughts on finding a character’s personal reality, how working with Julia Coffey alters his approach onstage, and what audiences should keep an eye out for in his turn for the dramatic:

Your character in RICHARD II, Henry Bolingbroke, is a pretty serious guy. Do you find any parallels between Bolingbroke and the many iconic clowns you’ve played under the tent?

Bolingbroke is maybe one of the least clown-ish roles I’ve played. Whenever I play a clown I always try to look for moments of seriousness, where I can ground the character. When I play a serious character, it’s the opposite: I’m looking for moments of levity and humor. Bolingbroke is one where I’ve totally raked through the ground of that part and found almost nothing in terms of levity.

Is that disheartening?

No, I find it fascinating. That heaviness allows me to put my focus elsewhere. That’s really my method no matter what: where’s the reality in this character? Where is this character grounded? Bolingbroke is who he is. He’s going to just bulldoze forward. So, I’ve had to look for other interesting things to do with that character. Humor is not something he seems to be interested in.

What are some of those other interesting elements you’ve found?

The more I analyze the propulsion of the play and Bolingbroke’s track — the way he b-lines to the finish line, goes after what he wants, and gets what he thinks he wants — my main job as Mark the actor has been to play tug of war with Bolingbroke the character as he bulldozes his way down the track. Where are those moments when he doesn’t always make the decision to usurp Richard and go after the crown? In a way, I fight with my own character. We’re always in a mental battle. It’s almost like I, Mark, am the good angel on his shoulder… but Bolingbroke just keeps moving forward. Mentally, RICHARD II is a much harder play than THE TAMING OF THE SHREW is for me. Bolingbroke is such a gravitational force of his own that I’m always looking for something to slow him down, to change his course. That’s what makes it interesting for me.

How does Julia Coffey’s casting as King Richard affect the way you see the relationship between Bolingbroke and King Richard, or your relationship together as actors?

I’ve spent a lot of the rehearsal process trying not to treat her differently than I would a male actor playing the part, for example, resisting the urge to call her “she.” But I always look for the love in character relationships: is there a lack of love, and that’s what breeds hatred between them? I tried to ignore the gender difference of Julia and King Richard, thinking, “that’s my cousin — my male cousin — whom I love; or, maybe we grew up together and were close but now we’re far apart.” But later I wondered what would happen if I did think of Richard as someone I could actually love in a deeper way than I might within a heterosexual male-male relationship? What if that actually buys me something onstage, in terms of how painful it is to usurp Richard? Within Bolingbroke’s story, I’d think, “I love you, but you are really messing up and I have to take the throne to do what’s right for this country.” In that sense, it feels like I’m cheating to see Julia as a woman in the role of Richard, but it helps me because the fallout can feel more heartbreaking. I can better relate to it as a breakup.

So, you’d say Julia’s being female makes it easier for you to put yourself in that headspace?

I hate to admit it. I’d like to think that if it were a man in the role of King Richard, I could still put myself in this headspace… but it’s almost easier as a heterosexual male to feel the complicated raw emotion of perpetrating these terrible things with such depth against a female who I have great affection for. Offstage, I like Julia as a person, too. All of those elements are useful onstage. It’s a tragedy. And Julia’s so good at emotionally diving into the part, so as we watch her move through the heartbreak in those moments (“now mark me, how I will undo myself”) I just let her be who she is but say the male pronouns as written.

For those who have seen the production, the dance of Bolingbroke’s army can come as a surprise. Can you talk to us about that scene?

Davis (Director, RICHARD II) always has such great vision. His idea with that scene was to find a way to physically represent the series of events happening offstage, the things we hear about between scenes. Bolingbroke is steamrolling through the country and taking all these castles. People are pretty much giving up without a fight — laying down and letting him, or outright joining his cause. So Davis thought, ‘is there a way we can physicalize this?’ Tracy, our choreographer, came into the rehearsal room with this dance. It wasn’t collaborative, because it didn’t need to be. It was exactly what needed to happen. A lot of audience members want to clap, like, “oh, yay! A dance!” But all we try to do in response is shoot them hateful looks and shut. it. down. The movement is all about taking castles with a show of force and violence, so our job is to dance and give people the death stare. Don’t you dare clap!

Are there other visual elements like this hidden in the show that audiences should know about?

A thing to pay attention to is Davis’s staging. This production is like an opera, where characters are telling huge swaths of story through their actions and placement on the stage. Most of Shakespeare has virtually no subtext, but a big part of RICHARD II’s second act, when Richard concedes, is subtext. Almost no one is meaning what they’re saying, which is so rare in Shakespeare. Pay attention to what people are doing rather than saying. For instance, Bolingbroke is saying to Richard, “we’re gonna let you stay king, we’re just here for my land,” which is a complete lie. At the same time, Richard is saying, “it’s cool, I got you,” but he also knows his cousin is lying, and he’s not actually cool with it. Huge chunks of text are facade. It’s so fascinating.

Why do you think Shakespeare wrote the play in this way?

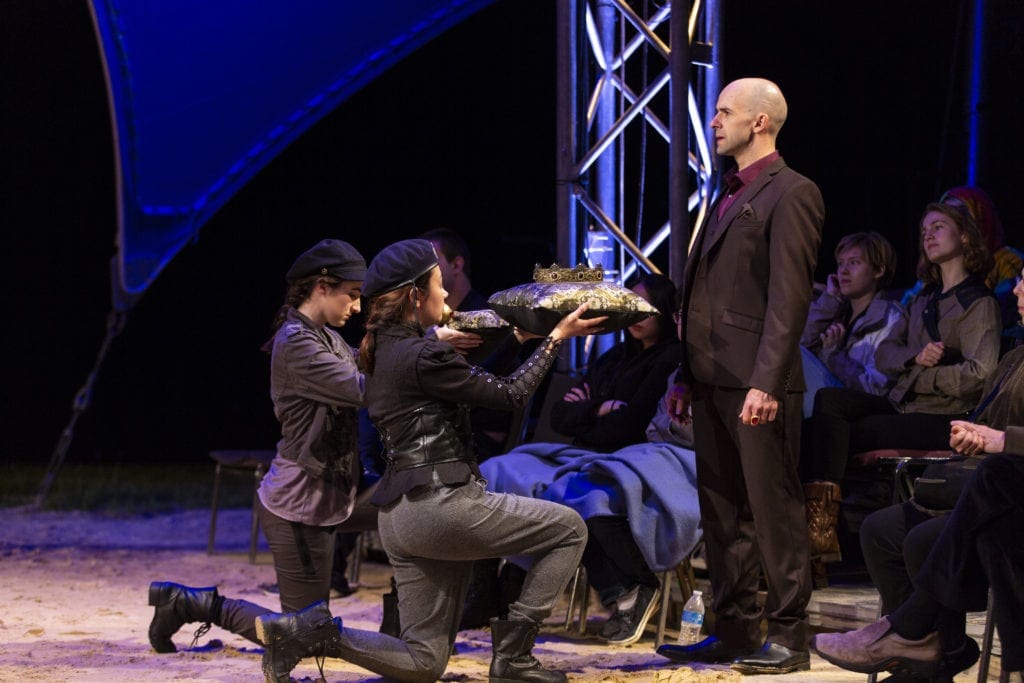

I think in Shakespeare’s day, audiences would have known exactly what was happening in this play, so there’s this overarching dynamic of wanting to hide the reality of characters’ desires and actions, even as the characters themselves – and the original audience – would have known full well what was really going on. As modern audiences, we’re not used to that and we don’t really know the history in the same way Shakespeare’s contemporaries would have. I think Davis has done a really great job of keeping the subtextual story alive in his staging. There’s clearly something else going on and he preserves the dramatic tension between text and true events, until, all-of-a-sudden, they slam together. And if you’re not paying attention to the staging, it can feel like you’re missing out — like a rubber band that snaps, skipping to the next dramatic moment. Another moment to pay attention to is when the crown comes out. When I move to put the crown on, that staging is not written in the script, but in the abstract we’re using a literal action to show the meaning behind the text, and to show the very real stakes of what’s actually happening in that scene.