Posted July 19, 2018

![]() Originally published on July 19, 2018 by Jesse Green in The New York Times (“Review: Taming ‘The Taming of the Shrew’ Under a Tent”).

Originally published on July 19, 2018 by Jesse Green in The New York Times (“Review: Taming ‘The Taming of the Shrew’ Under a Tent”).

When last we dropped in on Kate, Petruchio, Bianca and the gang, they were contestants in some kind of surreal beauty pageant, riding around on bikes and making no sense. That’s what “The Taming of the Shrew” had come to in a 2016 Shakespeare in the Park production directed by Phyllida Lloyd.

To be fair, those were end times for “Shrew”; no one knew what to do anymore with a comedy that turns on the humiliation, torture and probable rape of an “irksome brawling scold.” (In Anne Tyler’s novel “Vinegar Girl,” released that same summer, Kate tames herself.) Ms. Lloyd evidently hoped that an all-female staging — the men were played by women in drag — would pluck the stinger from the wasp, to paraphrase Petruchio. Instead, the sweaty desperation of the effort exacerbated the problem and made it look intractable.

Two summers later, with the #MeToo movement having exploded in the interim, it seemed time to say that “Shrew,” for all its perverse pleasures, should be left alone, in either of that phrase’s meanings. Do it as written and live with it, or don’t do it at all.

I’m happy to see that in adapting the play for the Hudson Valley Shakespeare, the director Shana Cooper felt differently. Her “Shrew,” playing through Aug. 24 under a tent on the grounds of the Boscobel House and Gardens here, finds an exhilarating new way to look at the comedy through modern eyes while remaining true to its language and, arguably, its intent.

Not that its intent is so clear. “Shrew” is a shaggy, youthful play — Shakespeare was still in his 20s when he wrote it — and can be pruned into various shapes. In Ms. Cooper’s staging, the topiary figures of a man and a woman that at times flank the dirt floor of the playing area, connecting it to the riverine flora beyond, suggest the shape she is after. For her, “Shrew” is a parable of discovery in which two misfits find, beneath the social construction of love, its natural contours.

Aside from the usual heavy trimming, the director has taken only a few textual liberties to get there, mostly at the end. The infamous speech in which the tamed Kate says she is “ashamed that women are so simple” now finds her ashamed that “people” are. Otherwise, Ms. Cooper reorients the play through her psychological framing of the action. Like Waze for Shakespeare, she offers an alternative route through the usual terrain.

The key to her interpretation is that Kate and Petruchio are (as she writes in a program note) “radical souls.” Kate (Liz Wisan) is not a termagant for nothing; she is protecting the slight freedom she has as a wealthy man’s daughter. Though instantly drawn to Petruchio, she’s too smart to trust him, or even herself; hostility is not her flesh but her armor.

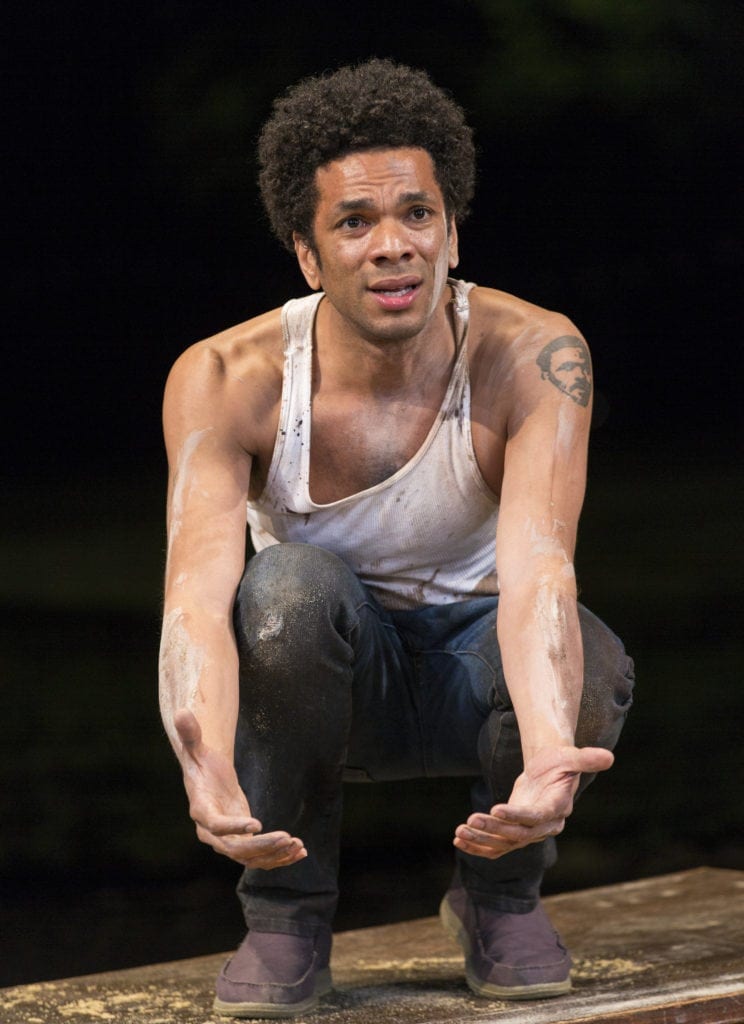

Likewise Petruchio (Biko Eisen-Martin) is instantly drawn to Kate, not merely to her money. (When he calls her “the prettiest Kate in Christendom” he is not, for once, being sarcastic.) The “taming,” which is at first a sexy, mutual game and only becomes grim when he fears he is losing, is thus not a punishment but a test. Petruchio wants to know whether Kate can truly love him despite her natural defenses. He does not so much ask “Will you obey me?” as “Will you soften your pride enough so that I can make you happy?”

And she, in essence, asks the same.

Their common enemy is marriage as it is traditionally arranged in their time — and, often enough, in ours. Ms. Cooper’s production shows us exactly what this means in its treatment of younger sister Bianca (Britney Simpson), who cannot wed until her older sister does. The scene in which suitors vie for her hand by trying to top one another’s financial offers is staged as an auction, complete with paddles. When Bianca does marry, even though it is to the suitor she most wanted, the girlish glee of independence drains from her at once.

What Kate models is thus not subservience to a man but a remaking of love through humility instead of humiliation. She no longer tells just wives to “place your hands below your husband’s foot,” but all spouses of any gender to do so, beneath “your partner’s.” The taming must be mutual and voluntary; you have no doubt that, should Petruchio try to spank her again, she would walk off into the landscape — as she does after their first encounter in this production — with her middle finger aloft.

That landscape does part of the work here. Like all of the festival’s offerings, “Shrew” — running in repertory with “Richard II” and “The Heart of Robin Hood” — benefits from its environs. The awesome view through the semicircular tent openings of the Boscobel grounds, Constitution Marsh and the Hudson River beyond suffices for the eternalities; the production can afford to be more improvisatory, frolicsome and of our time.

Ms. Cooper sees to that with a mostly young, eight-person cast, closer to the ages of the characters than we usually get. Ms. Wisan is an ideal Kate for this production, whip-stinging and whip-smart but deeply interested in men. And Mr. Eisen-Martin provides plenty to interest her, with his collegiate gamesmanship and boyish good looks, still slightly unformed. When love overtakes him unexpectedly you believe, as if for the first time, that he does what he does “in reverend care of her.”

These adjustments still can’t answer all the problems that “Shrew” keeps raising. (Worse almost than starving Kate is Petruchio’s coming late to the wedding she has finally decided to relish.) And Ms. Cooper’s carnivalesque staging — stuffed with comedy bits, golden oldies, pop culture references, cross-dressing, sprightly costumes (by Ásta Hostetter) and the “Kiss Me, Kate” song “Tom, Dick or Harry” sung fetchingly by Bianca — sometimes seems like it’s trying too hard.

Still, with the sky behind the actors slipping from pink to mauve to purple as the story itself grows darker, it’s hard not to have rosy feelings about this “Shrew.” It nearly makes you believe that within the same oldfangled men and women we’ve known for centuries, new people may really be ready to emerge.